This article is focused on the developments that have happened within the K-pop idol industry which have radically changed the way that K-pop agencies, broadcast companies, and fandoms operate. It's mainly focused on the time period of 2003-2018, the fifteen years that spanned the 2nd generation of K-pop idols (2003-2012, starting with DBSK) and most of the 3rd generation (2012-present, starting with EXO), and the transformations that have taken place during this time. And, to make it clear, I am primarily focusing on the K-pop idol industry and its production aspects, so other K-pop artists (like PSY) or other K-music (rock, hiphop, trot, indie) or Hallyu-wave phenomenon (K-drama) are beyond the scope of this article. This is an OP-ED (opinion editorial) piece focused on how trends in the creation, production and commercialisation of idol groups have changed in the industry, and projections into the future.

1) Super Junior and the rise of large idol groups.

Prior to the debut of Super Junior, most idol groups followed the U.S. industry's model of having smaller groups of 3-6 members. Super Junior, however, started off with 12 members during their 2005 debut - more than twice the average number of members in an idol group. This was further expanded to 13 members in 2006 with the addition of Kyuhyun. At the time, many industry pundits were doubtful that such a large group could be managed and become commercially successful. However, the successful debut of Super Junior paved the way for other groups with large numbers of members to be formed - most notably the 9-membered Girls' Generation in 2007 (widely seen as the 'female Super Junior' at debut [1, 2]).

The experiments with larger groups in K-pop were also paralleled by experiments in the J-pop idol industry at the same time. Producer Akimoto Yatsushi began a project to create the largest female idol group in Japanese history in 2005, which we now know as AKB48. The Japanese band EXILE also started auditions for 2nd-generation members to be added to their original group of 6 members in 2006, and have since expanded to 15 active members as of 2019.

Other agencies in the K-pop idol industry began experimenting with larger-numbered idol groups throughout the 2nd generation. After School, by Pledis Entertainment, debuted in 2009 with the concept of rotating members with an admissions and graduation system, similar to AKB48. They had a peak of 9 active members in 2012. DSP Media launched the 7-membered girl group Rainbow also in 2009. However, this growth in group numbers really came to the forefront in the third generation of idols, where groups numbering 7-14 members are not uncommon (EXO, AOA, TWICE, I.O.I, Wanna One, IZ*ONE, Seventeen, Oh My Girl, etc.). Partially, this was due to the growth of the K-pop idol industry as a whole and the increase in the numbers of trainees preparing for debut, requiring larger idol groups to be formed or more severe dropout rates.

Looking forward into the 4th generation of idol groups, the K-pop idol industry is headed towards a crisis. The root cause behind this trend is the massive increase in the number of trainees hoping to debut. However, with the idol market already being saturated, the number of spaces for trainees to become commercially-successful idols are reaching a hard limit. Debuting more trainees in a group can be a temporary patch to absorb the excess supply, but more numbers of active idols also require a corresponding increase in the expenses for management companies. Only the richest companies will have the resources to sustain large groups, especially if the idols are not immediately successful upon debut. This implies that a change will need to happen soon, and new innovative models of structuring idol group management are required. Perhaps rotating rosters (similar to the AKB48 or After School model) might make a resurgence, as SM Entertainment is trying with its NCT groups. Perhaps groups could be sent overseas to expand into as-yet unsaturated markets (like the Latin music market). Or perhaps more should be done to cut off the trainees at an earlier stage before debut. Which brings us to...

2) The Rise of Debut Survival Shows

I need to clarify a point here about the differences between audition shows (like K-pop Star) and debut survival shows (like the Produce series). In audition shows, members of the general public compete to enter a K-pop agency and either release a record immediately or become one of their artists or trainees. In debut survival shows, trainees who are already (mostly) in an agency compete with each other to be the ones selected for debut as an idol.

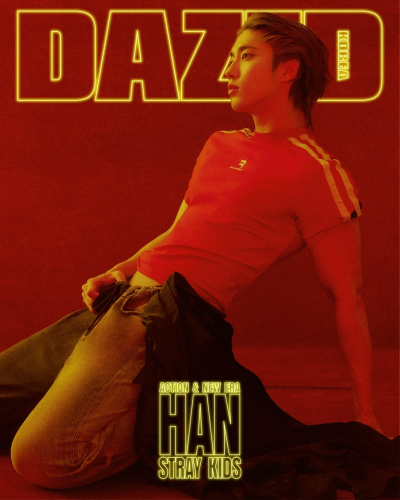

Now, survival shows are nothing new. They've been done ever since the start of the 2nd generation of idol groups. Most notably, the members of BIGBANG, 2AM + 2PM (One Day) were all selected through survival shows (though they were filmed as documentaries of the training and debut process). More recently in the 3rd generation, the groups WINNER, iKon, SF9, Monsta X, Momoland, VIXX, TWICE, Pentagon, Seventeen, Stray Kids, In2it, Uni.T + UNB, I.O.I, Wanna One, and IZ*ONE were all formed or went through survival shows in order to debut. Mostly, these survival shows are done in-house, within one particular agency - the main exceptions to this being the Produce series and The Unit: Idol Rebooting Project show. In many cases, the rise of debut survival shows are a response to the increasing numbers of trainees at entertainment agencies - a way for them to cut down their number of trainees to form an idol group of manageable size. Even so, the large majority of groups formed through survival shows tend to feature above-average number of members, indicating that this might be only a temporary solution for that problem.

The benefits and disadvantages of survival shows are quite clear - by involving the audience to participate in the selection and voting process, the companies can build fan followings for a group prior to debut. This in turn makes it more likely for the group to have a successful debut and begin raking in the cash quickly - although this also depends on the amount of resources and exposure the company can generate for the group amongst the larger general public instead of merely within its' own company stans. However, the costs of producing survival shows are also much higher than merely conducting internal selection tests that are not broadcasted to the general public, and then launching traditional publicity campaigns for the newly-debuting group. Also, if there is significant audience disagreement with the final group selection, this may lead to a divided fanbase and a rise in anti-fans from the very beginning, or people criticising the company running the selection process.

The rise of the multi-agency survival shows like the Produce series, The Unit, and the failed MIXNINE show also indicates another trend happening in the industry - the increasing collaboration between smaller companies on mutual projects as a business strategy to survive in the industry. However, with many of the idol groups containing former-I.O.I. members achieving relatively limited successes with their home agency groups, it is questionable how sustainable this business model is. It is highly possible that one member's popularity because of a multi-agency survival show does not translate well into popularity for the whole group he/she is in, without additional factors being involved. On the other hand, the success of Chungha as a solo artist suggests that perhaps without having other group members to dilute the popularity effect gained from taking part in the Produce series, much of the idol's popularity can be retained. This phenomenon and likely effects would need further verification and evidence, based upon the other I.O.I. (Jeon Somi) and now Wanna One artists' track records going solo versus debuting as a group with other home agency idols.

Another trend that debut survival shows are highlighting is the blurring of lines between traditional broadcast companies and idol management agencies. As companies and conglomerates merge together, it is becoming possible for one company to expand and integrate vertically up and down the entertainment industry's supply chain, to create an entire ecosystem of media content that is self-contained. For example, MNET is the broadcast company that has collaborated to create many of the survival shows listed above, most notably the Produce series. But MNET's largest shareholder is the conglomerate CJ ENM, who also is the majority shareholder of a number of different artist management agencies such as Stone Music Entertainment (former management of Wanna One and IZ*ONE), Jellyfish Entertainment (who manage gugudan), and MMO Entertainment (former agency of Kang Daniel). CJ ENM later created a number of management agencies specifically dedicated to manage the groups that emerged from their survival shows, such as Wanna One, IZ*ONE and fromis_9. Therefore, some industry reporters are arguing for CJ ENM to be included as one of the 'Big 4' because of the variety of broadcast and management companies they own. In a parallel development, the widespread availability of social media platforms to broadcast User-Created Content has allowed many traditional management agency companies to take their first steps as broadcast companies. Which brings us to...

3) Social Media, Communication Patterns, and Online Idols

The most wide-ranging change in the idol industry, of course, is the advent of social media and the way it has changed fandom-idol interactions. This is a huge topic worthy of a full article by itself, but I'll just highlight some of the more important changes that have occurred.

Firstly, as mentioned in the earlier section, the availability of social media platforms allows management agencies to now start creating broadcast content that is self-produced and self-edited in-house. An example of this would be the TWICE TV series produced by JYP Entertainment. They created it in-house to showcase TWICE behind the scenes or on trips, broadcast it on VLive and YouTube, and are even selling it as DVDs on Amazon. Other management agencies are also doing the same with shows such as MAMAMOO TV or Blackpink House. However, this is of course an expensive undertaking, so most management agencies are still relying on partnerships with existing broadcast companies to create reality shows, similar to the collaboration models that created most of the reality shows featuring groups of the 2nd-gen idols and early 3rd-gen, such as KARA Bakery, SNSD Factory Girl, and WINNER TV (all of which, incidentally, were produced in collaboration with MNET).

Secondly, the communications relationship between idols and fans have changed from one-way broadcasts to two-way dialogue. Fans of the second-generation idols would remember that most of the ways in which fans got to know their idols was through radio or TV broadcast shows that were fansubbed and posted on video-sharing sites. It was pretty much a one-way broadcast from idols to fans, and the only way of responding (if you weren't in Korea) was to write letters or send gifts. However, with the dawn of livestreaming apps such as Twitch and VLive, or personal social media channels such as fancafes, Twitter and Instagram, fans could communicate with their idols directly, from all over the world.

The broadcast shows that featured the 2nd-gen idols usually had to go through an editing process before being broadcast (even the people who called in to radio Q&As were usually pre-screened). The agencies could filter the content for anything that would affect their idols' image. However, instead of just having pre-edited and managed content, idols of the 3rd gen can now chat directly with the fans in real time, in an unfiltered manner. Which can lead to a stronger feeling of intimacy and closeness, and replicate the effect of a fan meeting or live radio Q&A session without having to be physically nearby. And fans themselves often appreciate the 'dorkiness' of idols who show their real selves and personalities, without the filter of management. If handled well, there could be a much faster buildup of a fanbase, as BTS, BlackPink and TWICE have shown.

While idols having direct access to two-way communications with fans is a great way to build popularity, it also comes with risks and problems. For one, there have been multiple incidences where an idol's un-edited and un-supervised direct communication with fans has led to upset and controversy - most recently, TWICE's Sana's comments about the end of the Heisei era, for example. A second problem that once a certain level of fan-engagement through social media becomes the norm, it can be relatively more pressuring on idols (especially introverted and quiet ones) to maintain communication. Thirdly, control and activity over social media channels may become a weapon in or cause of disputes between artist and agency, as was seen in Kang Daniel's cases [3, 4]. Fourthly, of course, is that social media can become a channel where anti-fans have just as loud a voice as fans, and so, idols get exposed to criticism and hatred more, which can affect their mental well-being. Fifthly, from a management perspective, the best way to monetize social media engagement for idols has not been worked out completely. Many companies are trying different models, from paid subscriber/premium channels, to online gifts in livestream chats. Having your idols spend a significant portion of their time engaging with fans without getting any monetary rewards is always a tricky problem to solve.

As social media continues to penetrate our lives, moving forward into the 4th generation of idols, there are constant experiments being conducted as to the best way to manage and monetize social media. Some idols such as MBLAQ's G.O. transition successfully into Broadcast Jockeys and add another revenue stream to their income. At the same time, with Korea being at the forefront of the mobile and digital technology wave, innovators are also looking for new models of creating idols that rely on new technologies such as Web 3.0, 5G mobile networks, Virtual Reality and the Internet of Things. We've started to see glimpses of 'virtual idols' becoming more prominent, starting from Japan's experiments with Vocaloid 'idols' such as Hatsune Miku, to the recent K/DA Popstars music video created by League of Legends. SM Entertainment also partnered up with SK Telecom to exploit 5G mobile technologies in order to stream holographic Kpop idol videos to fans. As we move into the fourth generation, the ways in which Kpop idols will be broadcast, marketed, and interact with fans online will become increasingly complex. It's anyone's guess what it would take to succeed as an 4th-gen idol in the post-social-media, 5G-enabled media world.

Conclusion

There we go. Three different aspects of how the idol industry has grown and changed over the course of the last 15 years. Now of course, there are many other trends in the industry which have also changed over the years. But this article was primarily written to give people a sense of both the past and the future. The Kpop idol industry has grown tremendously in the last 15 years, but now faces many new challenges. The local South Korean market is almost fully saturated, and many smaller or mid-sized agencies will have to innovate to survive. What forms those innovations take, and how monetizable they are, will likely determine the future of the up and coming groups of the fourth generation of idols. And failure to innovate, or risks taken that don't work out, may spell the downfall of even large companies.

What do you think? What trends do you see happening in the current generation of idols, and how will that change the future of the 4th gen? What lessons from the past can we learn, in order to better manage the present or prepare for the future? Comments and discussion welcome.

SHARE

SHARE

This is a well written and intelligent analysis--an excellent model for contributions to allkpop.

4 more replies